The Men Who Went Through Hell with Sgt. York {Part One}

Appreciating Those Who Supported the Legendary World War One Hero

The following article was my senior thesis, completed for my application for graduation from the History department at Bryan College, 2022. It highlighted a deep passion of mine for social history and the stories behind the face value. I utilized my time, resources, and friends within the Tennessee State Parks Department to track down myriads of primary documents, photos, and interviews to answer the question: “what really happened on the day that would make Alvin York famous?” This was an excellent opportunity for proving my abilities within the fields of historic research as I had enjoyed spending several years as a seasonal recreator at the Sergeant Alvin C. York State Historic Park, and at the time planned to become a State Park Ranger, hopefully at the same.

The story of Alvin is a well-known one in Tennessee. He is a state hero, a requirement within state history standards, and his story as told within the film is an endearing classic to this day. However, as I illustrate within this thesis, the story is not as cut and dry as it is often romanticized to be.

The day October 8, 1918 in the area of Chatel-Chéhéry, France was not meant to be one of individual historical value. War had engulfed the world for the last four years, and all eyes were focused on larger events nearby, mainly the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The push to force the Germans out of France was well underway, as the offensive had begun on September 26, targeting German holdings in the Argonne Forest and along the Meuse River. This was the closing days of World War One, as demoralized German troops found themselves lacking the strength and means to continue so far from home, and Entente forces (hereafter referred to as Allied forces, being the more familiar phrase) surged forward, bolstered by American soldiers.

Within the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, over one million American troops would advance, making this the largest maneuver by the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). This was a definitive part of the war but harrowing as well. Casualties would run high, with over 120,000 overall casualties, and more than 26,000 American doughboys killed in action.

With the stakes placed so high, there was great room for heroism. Over fifty Americans would receive the Medal of Honor, the highest military commendation, in recognition of their actions within the Meuse-Argonne Forest. It is the purpose of this thesis to focus on one of these men and the heroes who served with him.

Sergeant York (then an acting corporal of a small squad of men), would distinguish himself within a small, and seemingly inconsequential skirmish within the Meuse-Argonne, however his actions would be some of the most remembered of the entire war. Afterwards, he was celebrated as an American hero, reaching legendary status in today’s recounting of his actions.

On October 8, 1918, Alvin York was part of a small squad sent from the larger party of the 328th Infantry, Company G, mobilized to help relieve the famous Lost Battalion within the Argonne Forest. When the squad fell under enemy fire, York was credited with bravely paving the way for safe passage, helping to capture 132 German soldiers, and killing between 20 and 25 enemies along the way. For his bravery in what was later said to be an almost singlehanded rescue of his commanding officers and fellow men, Alvin was awarded the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Croix de Guerre, a distinguished French military honor.

Today, as school children in the United States learn of World War One and the major events that happened in this time in history, they are taught about Sergeant York and his heroism. In Tennessee, his home state, Alvin is a hero of both wartime and peace. Tennessee state social studies standards include him as a highly influential Tennessean, commemorating him in their state history courses. In Nashville, the Alvin C. York Memorial commemorates his actions in a statue of him in doughboy attire on the grounds of the State Capitol. In his hometown, his farm has been converted into a state park to remember his legacy.

However, there is much controversy (both historic and current) surrounding Sergeant York’s fame, and it is this that will be discussed within this thesis. Two sides emerge in viewing and addressing Sergeant York’s Medal of Honor. One side claims that Alvin was deserving of his recognition as a national hero, and that additionally, his heroism ought to be lauded. The other side however argues that through accepting sole fame and recognition, Alvin successfully prevented the other men on patrol with him that day from ever receiving acknowledgment for their work and bravery on October 8, 1918.

It is the thesis of this paper that, arguments about Alvin’s story aside, these other men deserve to be remembered, and they should be honored for their sacrifice and bravery as well. Alvin may indeed deserve recognition for his work as a sharpshooter and squad leader on October 8, 1918, but the other sixteen men also deserve to have their stories told. It is the purpose of this paper to prove that telling the stories of these other men does not take away from Alvin’s glory, as glory shared is not glory diminished, and it often takes a team to make a hero. It is important to remember these sixteen other men and their actions on that day, as they were all heroes.

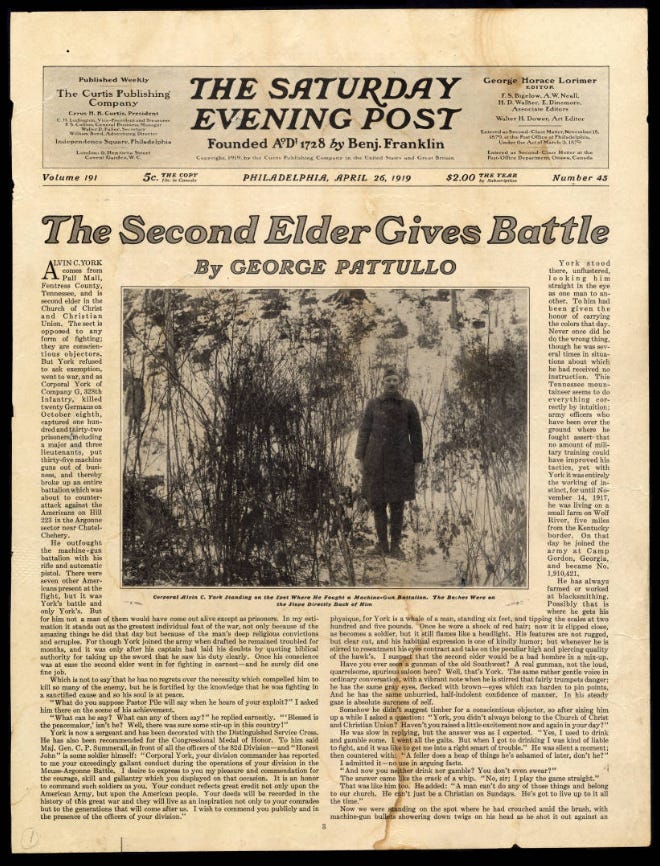

The story of October 8, 1918 broke on the world on April 26, 1919. George Pattullo, special war correspondent for The Saturday Evening Post, interviewed Alvin and published the original sensational story under the title, “The Second Elder Gives Battle,” highlighting the story of a conscientious objector turned war hero. It was this version of the story that was the first to be read and enjoyed by the American public, but many aspects of the beloved legend did not come until later.

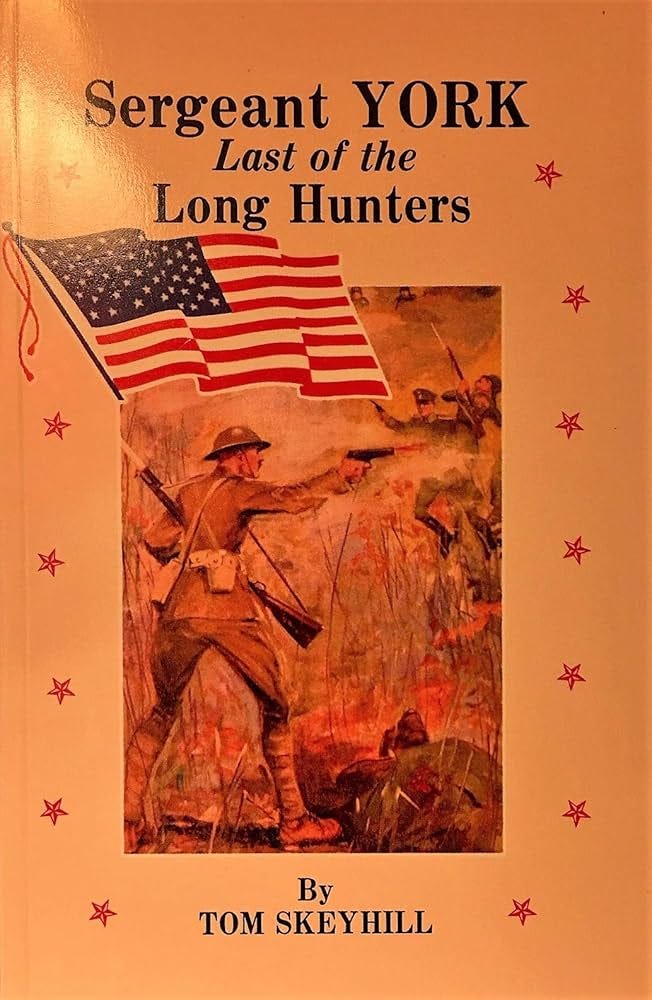

Thomas Skeyhill Jr. authored the famous book, Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters in 1930. This was credited as the first real biography of who Alvin York was and introduced him to an even wider audience. With sundry details such as Alvin’s “turkey shooting style” of killing charging German officers and linking Alvin to the ever-famous long hunters, it created an image of the war hero as an unassailable, unflappable character of cool head and fine aim. It is Skeyhill’s story that is the general view of Alvin that remains today

The story unfolds in a manner reminiscent of a western shoot out. As the 328th advanced to relieve the Lost Battalion, they fell under heavy enemy fire. The commanding officer, seeing they could not hope to advance until the machine gun nests had been subdued, charged a small group of two to three squads (accounts vary) to “put the enemy machine guns out of action.” When the group of men made to circle behind the hill on which the nests were stationed, they flushed two German soldiers, who ran from their advance. Going still further, they stumbled upon an encampment of German troops, in the midst of breakfast. Most of them being unarmed, the American troops were easily able to capture them with little resistance.

As they made safe the prisoners, troops on the hill were alerted to their presence, and opened fire on the doughboys from above. Six Americans were killed outright, and several more wounded. Suddenly Alvin found himself the lone man in charge, and in an advantageous position to return fire. While the other men hugged close to the prisoners, hoping to avoid enemy fire and keep them from escaping, Alvin opened fire himself, alternating shots with calls to the enemy to come down. After an intense firefight, he would secure the surrender of the hill.

After this, Alvin would line up his prisoners, and with the help of his men, would march them out of the forest to a temporary Army post. In all, Alvin was credited with 20-25 kills, the capture of 132 German prisoners, and the securement of Hill 233 (as dubbed by the AEF). For this, he was labeled a hero by the War Department.

The years following World War One would prove to be eventful for Alvin. He was first awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and then the Medal of Honor for the Army. Additionally, the French would award him the Croix de Guerre, or “Cross of War.” He then went on to more than military fame, catapulted to recognition by the Pattullo article. Upon return to the states, he found himself a national hero, and embarked on a tour of New York.

Making his way back to Pall Mall, Tennessee, and his family, he married the girl of his dreams and settled down. He and his new wife, Gracie (née Williams), were gifted a house and property in his home county of Fentress. Together they had ten children, eight of whom made it to adulthood. Alvin smithed and farmed on his property and spent his life trying to utilize his fame to bring progress to his beloved Wolf River Valley.

The war meant Sergeant York had experienced a bigger world than that of the backwoods of Tennessee, and to this end, he fought for schools to be introduced to benefit the Upper Cumberland. Having grown up in an agrarian household typical to the area, Alvin had managed to attain only about a third-grade education in between the demanding work of running a homestead. It was his desire that the children of Tennessee would have the opportunities that he never received and could break the cycle of perpetuated antiquity.

Fight is an accurate verb for this vision. Alvin’s decision to bring schools to his home was a charitable one, but not one often backed by the local officials, and he invested years wading through red tape and public disapproval before he saw any fruit. It was by his own words, “A much more terrible fight than the one that I fought in the war... And I couldn't use the old rifle or Colt automatic this time.” Instead, Sergeant York battled within the local and state offices of politicians, pushing to win over a culture resistant to change and the loss of its way of life.

It would be this that initially caused Sergeant York to slip out of national interest. Uninspired by his talks of the need for education in the underdeveloped reaches of the United States, people took their attention elsewhere. This was exacerbated by the fact that Alvin refused to cater to public demand to hear his war stories, which he regarded as trivial in the light of the pressing needs of his community.

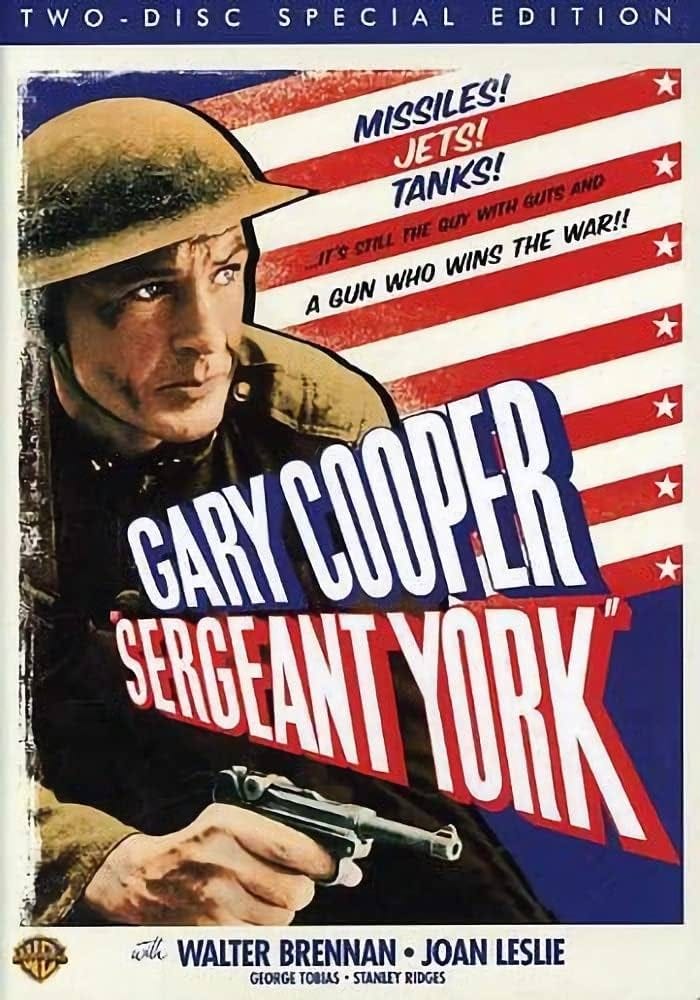

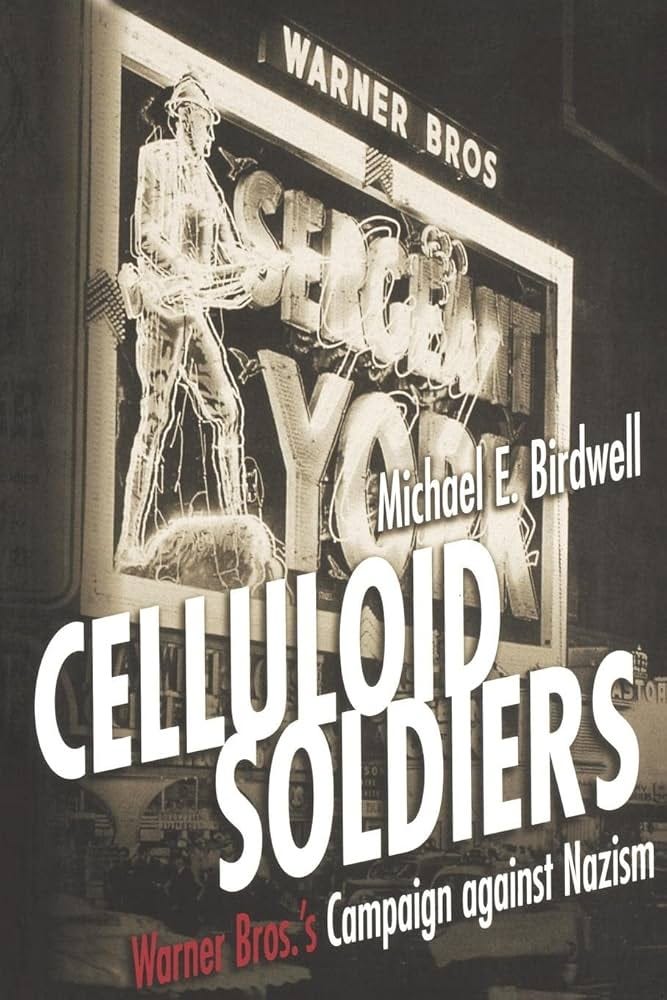

While Alvin struggled with relevance after the world turned back to peace, he eventually found new ways to return to the public eye. One of the most notable was the 1941 Warner Bros. film, “Sergeant York.” This film was in line with Alvin’s eventual pro-USA involvement view of World War Two and served as an opportunity for him to raise funds to start a bible school in the Wolf River Valley.

The movie was a massive hit, and an excellent form of war propaganda for those hoping to raise support for American intervention in Europe. His personal struggle with the validity of war “found new resonance in an America at odds over the recent European war, for York personified isolationist-Christian America wrestling with its conscience over whether or not to engage itself in the current war abroad.” Thus Alvin would end up in the limelight again, once more representing what America was and what it hoped to be.

While Sergeant York was busy making local, state, and national headlines, the other men who had served with him were mostly forgotten. They arrived home to no ticker tape parades, and the same or similar life they had left behind. For some, they returned to a life that was fraught with unemployment and bitterness. Tracked down in their later years, they expressed frustration that no one knew they were war heroes, and that Alvin received all the acknowledgment. Several would later receive recognition and smaller awards/commendations but would never attain the level of fame and national adoration as Alvin.

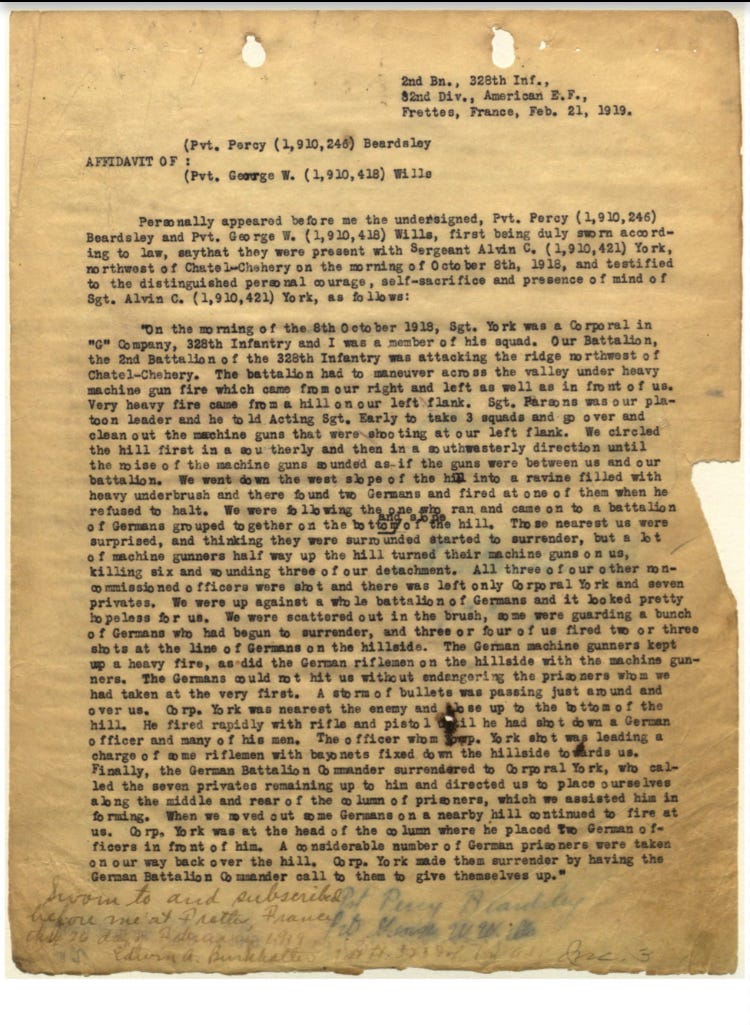

Requested to fill out and sign affidavits or statements several times within the process of reviewing the details of October 8, 1918, most of the other men were never awarded anything for their work. Military records signed by officers would only initially recommend Alvin for commendation, stating that there was no need to award the others.

On October 8, 1918, six men out of the seventeen-man group lost their lives: Corporal Murray L. Savage, Private Maryan Edward Dymowski, Private Carl Frederick Swanson, Private Nedwell ‘Fred’ Wareing, Private Ralph Weiler, and Private William E. Wine. These men were killed in the primary burst of machine gun fire that would send the squad scrambling for cover. They were buried later at the site of the battle by Chaplain John O’Farrelly of the 303rd Engineer Regiment, part of the 78th Division. They were exhumed for a second burial at a later date.

In addition to the men who lost their lives, Acting Sergeant Corporal Bernard Early, Acting Corporal Private William Cutting (who served under an alias, and will hereafter be referred to by his legal name, Otis B. Merrithew), Private Mario Muzzi and Private Patrick J. Donahue (sometimes spelled Donohue) would be wounded in action. Of these men, Early would be taken out of action with his wounds, sustaining three to five gunshots to the abdomen, one so bad that the men later recounted that they could see his kidney through the hole it made in his back. Merrithew, Muzzi, and Donahue would maintain some action, but would still receive medical attention after the skirmish. This left only a handful of men unharmed: Private Percy Peck Beardsley, Private Thomas Gibbs Johnson, Private Joseph Stephen Konotski (sometimes spelled Kornacki), Private Michael Sacina, Private Feodor Sok, and Private George W. Wills.

These men, as able, performed various roles on the morning of October 8, many of them keeping the prisoners from escaping and scattering during the chaos of enemy machine gun fire. They would line up the captured numbers and march them back to a temporary Army post, and then further back into friendly lines, Alvin in front with his pistol to a German officer’s back.

After the war, they would return to the lives they had left behind, resuming civilian duties. While Alvin received recognition for his actions, these men were overlooked, both in the War Department and the public eye. Unfortunately, due to this, there is a great lack of definitive knowledge as to what each man did during the years after the war.

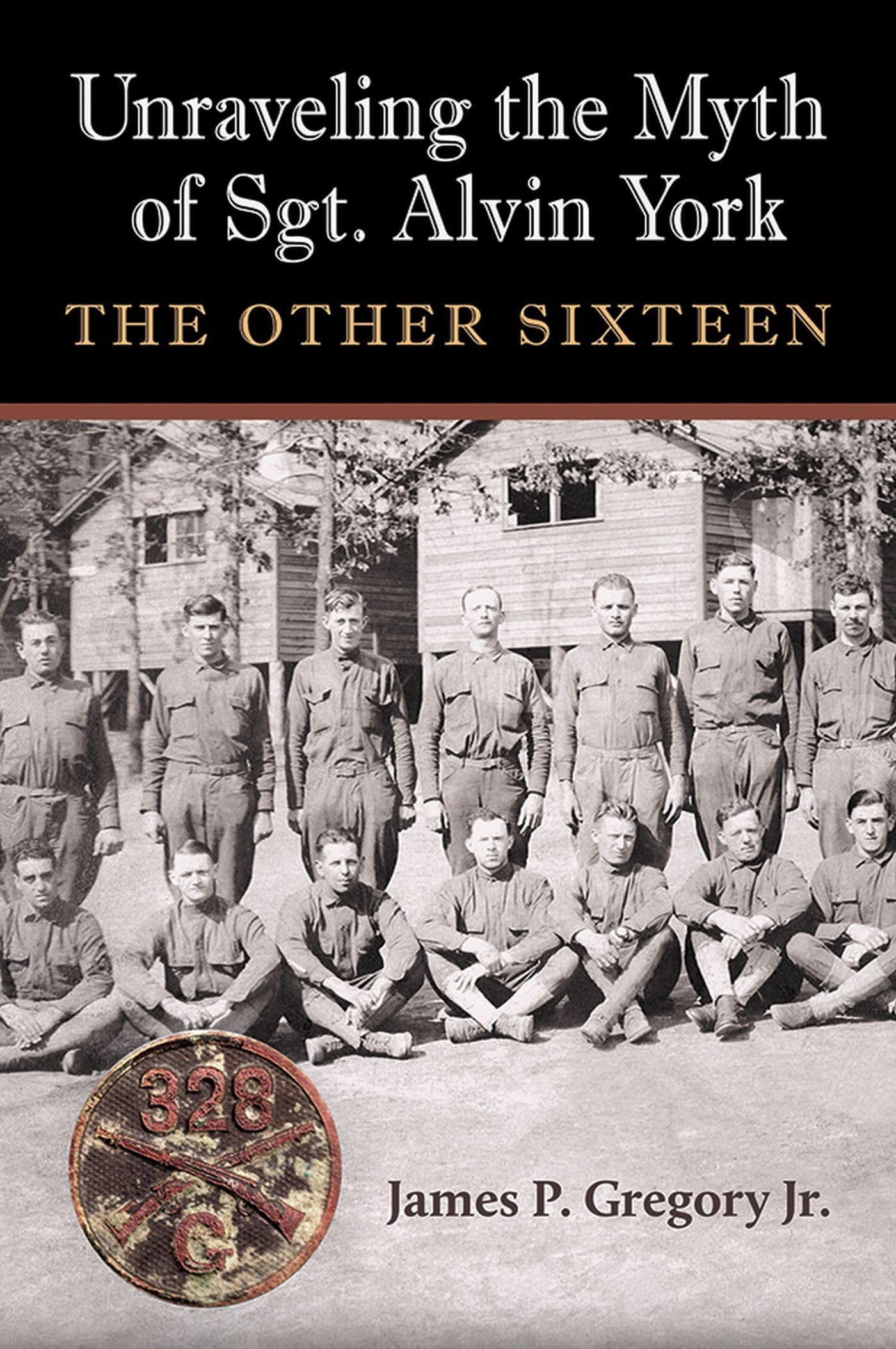

Few newspapers would have been interested in the stories of men who had only “assisted” a national war hero, and so only a handful of articles still exist to be found concerning these men. However, one syndicated submission that ran all over the nation was published just eleven years after the end of the war, in 1929. This article tracked down the still living and discoverable members of the original seventeen-man group, detailing their then-current lives, and their thoughts on Alvin. Additionally, James Gregory, Adjunct Professor of History at Rose State College, interested in the story of the other men who fought with Alvin, has been working with the families of these men to recover as much information about each one as is possible. Through this research, he has created the most definitive database available concerning the Other Sixteen. The following information has been drawn from both sources.

Otis Merrithew found work as a truck driver, crane operator, and then finally hospital guard. He married and had three daughters. Otis was the most vocal of the Other Sixteen, fighting for their recognition throughout his civilian life. He received the Silver Star for his actions in 1965, long after the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Corporal Bernard Early, the man originally in charge of the patrol spent approximately six months in the hospital for his war wounds and would return to the states after about a year in a French hospital total due to additional shrapnel removal surgeries. He ran a small restaurant in New Haven, Connecticut, and had four children. In 1929 he received the Army Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the actions of October 8, 1918.

Feodor Sok became a naturalized American citizen in November of 1919, after already serving his country of choice as a soldier. He also was a member of the Veteran’s Buckhorn Civilian Conservation Corps Camp on Grand Island, out of New York. Not much else is known of Sok, as he was unable to be found for the 1929 article.

George Wills worked as a feed wagon driver after the war. He married in 1920 and had three sons. No other information is able to be found concerning his life before and after the war, or his thoughts on October 8, 1918.

Joseph Stephen Konotski returned to the states in 1919 and married the following year. He and his wife had eight children. In the 1929 article he is listed as a mill worker in Holyoke, Massachusetts. James Gregory and the families of the Other Sixteen specify him to have worked for the American Writing Company.

Mario Muzzi worked as a baker at the National Biscuit Company Plant in New York City before the war. He returned to this job and married a woman by the name of Concetta. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1923. He retired and moved back to Italy, where he would die in 1978.

Michael Sacina returned to Manhattan after the war. He worked as a hat checker and operated a tobacco concession in the International Magazine Barber Shop. By his own recollection in the 1929 article, he felt after the war he had run into troubles, as since, “his return from the army he has had very bad luck, being out of a job quite often.” When the article was published, he had just been turned down for a position as a subway guard because of his diminutive stature. He married and had two children.

Patrick Donahue returned to the United States and picked up work as a mill worker, though his employment seems to have come and went. He received his Silver Star in 1945 for his actions on October 8, 1918. He never married.

Percy Beardsley returned to a simple life after the war. He moved back to his father’s farm in Knoxbury, Connecticut, and then ran it after his father’s death. The farm was one of the leading breeders of Devonshire cattle in Eastern America. Beardsley was also very vocal during his life about the story of the Other Sixteen, signing three separate affidavits or statements, and keeping regular correspondence with Otis Merrithew. He married but no children are listed as his offspring in any records.

Thomas Johnson was unable to be located for the syndicated article, but thanks to the work of James Gregory, it is now known that he returned to Lynchburg, Virginia. He spent a brief time as a stock clerk before moving west to Texas. As he grew older, he spent much time in and out of a veteran’s hospital.

As each man went home, most of them returned to the job they had held previously, or something within the line of the work they had held prior to the war. For the most part, they kept quietly to themselves as far as their time in the war was concerned. Some no doubt struggled with PTSD. Donahue is noted to have avoided speaking of his time during the war. Thomas Johnson spent his life, “nursing nerves shattered by his experience in World War I.” Within the 1929 article, it is stated that for George Wills, “not even his customers know that he is a war hero.”

As far as the public was concerned however, there was only Alvin on that day in the Meuse-Argonne Forest. The other men were as good as forgotten, but this changed when the announcement was made that a movie about Sergeant York would be produced. In the proceedings that followed said announcement, however, would come to light two very polarized views of the events of that historic day.

Currently, two schools of thought exist, with extremes on either end. Views range from believing Alvin a war hero handed to the Christian community by God, to the idea that he was a liar and a manipulator of the facts to claim his bit of glory. In between, the main factions either argue that Alvin deserved the Medal of Honor, or that he did not deserve it. Those who believe he did not deserve the Medal of Honor either believe he deserved nothing, or that he should have received a lesser medal alongside the other men. The key issues that rise out of this controversy are 1) whether Alvin did what he said he did, and 2) curiosity as to why the other men were overlooked while he received the utmost military award.

This controversy has been ongoing since Alvin was first awarded the Medal of Honor. While the men who served with him would sign various statements and affidavits, many would later claim that the story they put their names to and was subsequently published in the newspapers and history textbooks was not accurate. While the newly minted Sergeant York arrived home to a ticker tape parade and various meetings in New York, the others returned home to no standing ovation and no crowded piers. However, they argued that they had just as much a vital part to play in the events that had led to Alvin’s commendation.

Dr. Michael Birdwell, a history professor at Tennessee Tech, and curator of Alvin C. York’s Papers, was a leading modern expert on Alvin’s life. He delved deep into the legacy of this legendary figure, and in addition, within his book Celluloid Soldiers, he conducted extensive research into the Warner Bros. use of film as a source of propaganda against Nazism.

According to Birdwell, Warner Bros. began production of “Sergeant York,” in 1940, just a year before the United States would enter World War Two. The aim of the film became to create a movie that would move Americans to embrace the romanticized idea of good versus evil: one man fighting against the bad guys because it is the right thing to do.

As they built the script for the film, a team traveled to Pall Mall to shadow Alvin around his farm and learn more of the life he had in the backwoods of Tennessee. More notably for the purposes of this thesis, however, was the fact that Warner Bros. also sent out a gentleman by the name of Bill Guthrie with the job of locating family members, friends, and military members for their portrayal in the film. This included locating the Other Sixteen to acquire their signatures.

It was the desire of the film company to show Alvin’s time in the war accurately, and this meant depicting his war buddies. However, Guthrie found the other men to be less than interested in supporting a film about their wartime companion. As Guthrie located each man, he was met with stiff resistance to signing over portrayal rights unless a monetary figure was introduced.

Especially as Alvin began to attain recognition, there were feelings of bitterness exhibited by the Other Sixteen. Otis Merrithew was exceptionally vocal, advocating for recognition. He claimed that he was the one in charge of the squads, as handed over to him by Corporal Early, and thus deserved military honors as well. He would also make claim that the signed affidavits (argued as not actually affidavits but statements) were offered to each man as “a ‘supply slip’ for some article of clothing that was issued to them.” As such, he argued they had been manipulated and lied to in order to ensure that Sergeant York was the only one to receive recognition.

Merrithew kept correspondence with several men of the Other Sixteen and kept up a lively conversation with Gonzalo Edward Buxton Jr., who had served as a colonel in the AEF during World War One. Buxton was the commanding officer of the 328th Infantry Regiment in which Alvin and his fellow men served and would eventually write the official history of the 82nd Division.

Merrithew attempted to gain recognition as early as 1928 but was met with various loopholes and obstacles that he could not fathom. Invited to the War College at Washington’s general maneuvers, Merrithew broke his silence as to how he felt the actions on October 8, 1918 had gone, and asked Buxton for assistance. Buxton helped him receive the Purple Heart and the Silver Cross, but Merrithew never received the Medal of Honor alongside Sergeant York.

It was Merrithew’s argument that Alvin had lied to officials in order to receive solo recognition. The story that circulated was—to him at least—a hoax. Merrithew argued that instead of Alvin, he was the one in charge, and he was the one who deserved the major recognition. According to James Gregory in a personal interview, “Merrithew always swore up and down his whole life that he was given control of the unit and he got shot in the arm, but he stayed up and he was still in charge.” As he worked towards receiving his commendation however, he was urged by Buxton to curb his story and bring it more in line with the socially accepted saga in order to gain approval. Of course, one man may have a different story, but what is most interesting is how many of the Other Sixteen were willing to assist him and felt let down as well.

Overall, Merrithew’s was the most negative view of Alvin, but certainly not unique to the Other Sixteen. Instead this seems to have been the consensus of the other survivors. Among the familial archives of the men who served with Alvin can be found a letter from Feodor Sok to Captain Danforth, the patrol’s battlefield commander, expressing the desire to find a lawyer to plead their case with more power. Merrithew received a letter from his friend Matthew S. Payton in 1933, where Payton makes mention of their mutual dislike of Alvin. The syndicated newspaper article circulated in 1929 highlighted frustration among the men. George Wills was quoted as saying, “all of us fellows made the capture and should be credited alike, but Sergeant York seems to have got all the glory.”

Of the men who were there on October 8, 1918, the six killed received no posthumous awards. Five Silver Stars were awarded (Merrithew, Beardsley, Donahue, Konotski, and Wills), one commendation for gallantry (Sacina), and one Distinguished Service Cross (Early). Nothing comparable to a Medal of Honor was awarded to any of the other men, and it is to be noted that three men who survived (Johnson, Sok, and Muzzi) seem to have received nothing for their efforts.

It was this attitude that led to these men being so resistant to a film portrayal of their personages in what they viewed to be an erroneous retelling of history. Guthrie found it increasingly difficult to acquire their consent, and in the end, the film company opted to create a caricature in the character of “Pusher” within the film in lieu of continuing the battle to win these men’s permission. This character was to be Alvin’s companion within the film, a foil for humor and motivation for Alvin to move from conscientious objector to war hero.

Part two of this thesis will be published on April , 2025 and can be found under the Politics and History topic.