The Men Who Went Through Hell with Sergeant York {Part Two}

Appreciating Those Who Supported the Legendary World War One Hero

Part one of this thesis was published on April , 2025 and can be found in the archives for The Traditional Redneck under the Politics and History topic.

At this point in this discussion, it is necessary to take an analytical look at the claims made on either side of this argument. These claims on either side are based off the story that has circulated alongside other American legends for over a hundred years. Since it is wreathed in such fantastical facets, a deeper, more evidence-based look is in good order and there is no more tangible evidence than that of archaeological findings.

Thomas J. Nolan, former director of the Center for Spatial Technology at Middle Tennessee Tech University and a retired geography professor, alongside American military historian Brad Posey, with the assistance and backing of Dr. Birdwell from Tennessee Tech arranged a three-prong archaeological dig to locate the site of the battle on October 8, 1918, and build a more definitive view of the events. They published their findings within the Winter 2012 edition of the Tennessee Historical Quarterly in two articles titled “Where Sergeant York Won His Medal of Honor: An Example of Applied Geographic Information Science,” and “Re-Fighting the Meuse-Argonne: Alvin York and the Battle over World War One Site Commemoration.”

In their work, these men built a cohesive overview of both American and German accounts of the events around Hill 223 and utilized this to pinpoint a likely area for the site of the battle. They used a scientific approach for combing the projected areas and tagging the artifacts discovered. Making use of geospatial modeling through Geographical Information Systems (GIS), their team created a layered map of the areas surveyed, using historic documents from both American and German accounts laid over a map of the current landscape within the Argonne Forest.

With this approach, Nolan and Posey were able to locate what they deemed to be the location for the events of October 8 near Hill 223. As part of their overall approach within their three trips to France, the team aimed to not only locate the site of the battle, but also locate the graves of those killed, the individual firing locations of both Germans and Americans, and the geographical extent of the conflict.

For offering the most clarity, this section will start with a break-down of army units, frequently used within an explanation of the battle on October 8. For ease of explanation and comprehension, it has been chosen to start with the smallest unit and work upwards to larger units.

A squad is a group of eight to ten men, commanded by a sergeant. A platoon is a group of eighteen to fifty soldiers, or three to four squads, meaning that the group of men that were assigned to take Hill 223 on October 8, were just under this designation. They were a compilation of two to three squads (again, depending on the source consulted), at that time commanded by corporals. A company, such as Company G that was Alvin’s outfit, is three to four platoons, for a total of between sixty and two hundred soldiers. This designation can also be referred to as a battery, or a troop.

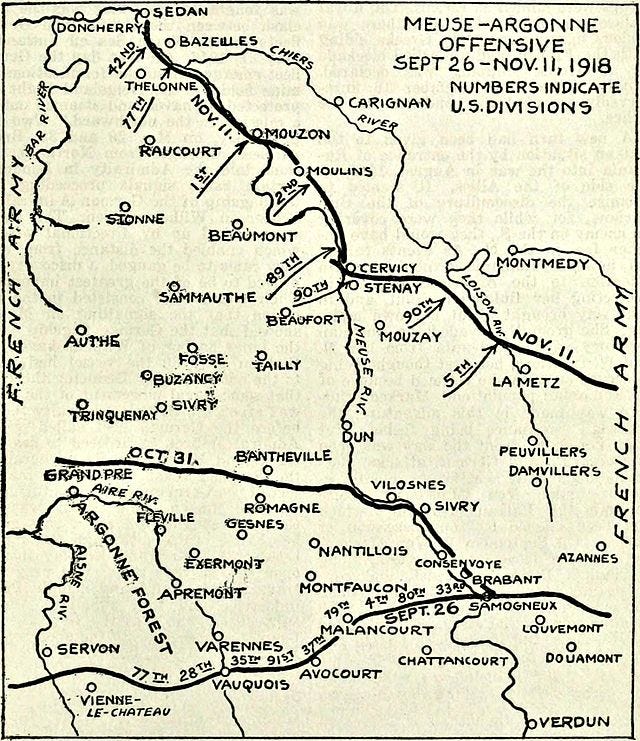

A battalion is three to five companies, with a wide varied total of 300 to 1,000 troops. A brigade, or regiment, such as the 328th, consists of three to five battalions, for a total average of two to five thousand troops. A division, such as the 82nd, to which Sergeant York was assigned, is a unit of three brigades, or a total of between ten and fifteen thousand troops. This is the highest designation for a large grouping of soldiers within the American Expeditionary Forces as this paper will go, as this explanation offers a breakdown of the most vital units of troop measurement necessary for understanding the archaeological evidence discussed within this section.

After Nolan and Posey were certain they had discovered the area of the conflict, they began a methodical search of the grounds for artifacts, finding over 2,600 in total. Their work revealed a large quantity of unexpended German ammunition near the hill that the AEF had dubbed Hill 223. This along with other debris indicated that this was a site of a large German surrender, where few shots were fired. This is in keeping with the accounts given within the affidavits signed by each man of the American crew.

As they continued their search, the team of archaeologists was able to build a prospective lineup of where each weapon wielding soldier was stationed within the battle, based on accumulations of expended weapon cartridges. Each weapon utilized a specific round, and bolt action rifles expelled empty cases to either the rear or side of the shooter, creating a pattern that can be used to not only locate a shooter’s position, but also the direction he was facing as he fired. A wide variety of German rounds were discovered (for example, 9 mm., pistol rounds and .77 mm for .77 mm field guns), with a notably smaller number of American rounds (for example .30-06 cases and clips and No .45 cartridges for a service pistol). Building a map of firing positions based on these casings and their locations, the team was able to determine that the Germans had been ambushed from the rear, and offered little resistance: there were few German casings to be found among the German debris, indicating that few of the men captured ever got a shot off. Additional rounds were found for German machine guns on the ridge facing Hill 223, and these were not faced out towards the location of the Second Battalion of the 328th but turned in towards the rear of the German line of defense, indicating that they were sited in to shoot at a target behind them.

American rounds were located on the side of the hill, with a large concentration of .45 casings grouped in one area that would have given a shooter adequate access to the machine gunners above. Nolan and Posey determined this to be the location for Alvin as he faced the machine guns and the subsequent charge of German troops. Based on these patterns, Alvin and his squad of chauchat automatic rifle wielding soldiers were on the hillside when the machine guns opened fire. This also confirms Alvin’s statement afterwards that he used both his rifle and his pistol.

Only a handful of other American rounds were gathered, and this is indicative that very few other members of the American squads were able to fire from their positions, due to the suppressing cover of the machine guns. However, it is to be noted that due to the archaeological findings, other men were clearly involved in the actions that took place just outside Chatel-Chéhéry.

From these archaeological surveys and military documents then, a more conclusive story of what happened on October 8, 1918 emerges.

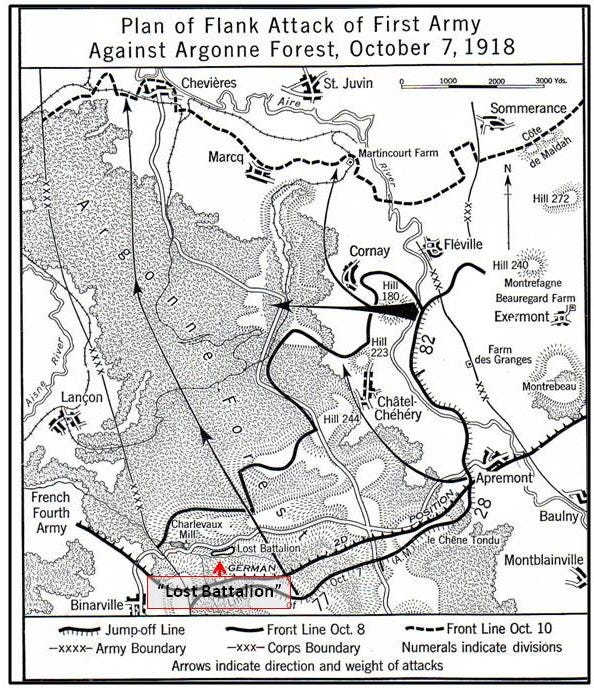

On October 6, 1918, Corporal Alvin, as part of the Second Battalion, 328th Infantry of the 82nd was placed into action to relieve the famous “Lost Battalion,” which was trapped within the forest. The plan was to flank via a western movement in order to then cut off the Decauville railway system that was supplying the surrounding German units. As records indicate, Company G (to which Alvin was assigned) was to be on the farthest left wing of this movement, closest to what was dubbed Hill 223 on military maps.

As the battalion advanced, they came under intense fire, and unable to press further forward, Sergeant Parsons ordered Corporal Early to take a sixteen-man squad around the site of fire and silence the enemy. Early took his men with Savage, Merrithew, and York overseeing portions of the team. As they flanked the hill, they flushed two Germans who led them to a group of the enemy. According to German reports, these were members of the Reserve Infanterie Regiment 210, assigned to guard “against attacks on …the heights west of Chatel.” Surprising this group, the Americans opened quick fire, but were ordered to cease by Early when he realized that the enemy was unarmed. The men surrendered and Corporal York moved his squad up the hill to guard the prisoners as the others below lined them up in rows and searched them.

Having heard shots from behind, the machine guns originally aimed at the position of the Second Battalion now turned their sights around and targeted the Americans behind enemy lines. This action killed six and wounded several others, but also endangered the Germans in the ravine. Being caught on the side of the hill, most of Alvin’s squad was unable to do much, as evidenced by the lack of American expended rounds, although there is no way to determine their overall involvement. However, Alvin does seem to have been in a position to do a little more damage in this instance, as shown by the .45 cartridges.

Eventually, the gunners on the hill would stop firing, and would be added to the number of those killed or taken prisoner. The previous noise had aroused other German officers’ interest and according to his own report, Lieutenant Max Thoma came running. As he rounded the corner, he came face to face with the situation, and the gunfire from the side of the hill. At the prompting of already captured Lieutenant Paul Vollmer, Thoma surrendered himself and his men as well.

This is a vastly different account from what is commonly told today, but one that in no way can be said to contradict the original statements taken from the Other Sixteen in 1918. These stated that Alvin was present “and with seven other men attacked and captured a Machine Gun nest, taking a number of Machine Guns and 132 prisoners, including four Officers.” It is interesting to note that this first set of statements, taken in order to recommend Alvin for the Distinguished Service Cross, highlights the fact that Alvin did not perform these actions alone. It would only be later, when the Medal of Honor became a possibility, that interest was placed on Alvin alone.

More than a hundred years after these events, it is this fact—that the original story was overlooked in lieu of one man—that has continued to fuel a rift between those who adore or hate the name of Alvin C. York.

Current descendants continue the sentiments of their ancestors. These families hold to the statement that there is more to the story of that historic day. According to the great-nephew of Bernard Early in a news article in 2008, “No one knows exactly what happened, but it wasn’t a one-man effort.” In the hopes of helping their ancestors receive the praise they are so rightly due, these families have come together to compile a database of primary sources and have worked with James Gregory as he penned his book The Other Sixteen, to be published later this year.

Gregory aims to tell the story of the other men on that fateful day because in his mind, glory shared is not glory lost. It has been his goal to follow the trail the Other Sixteen have made in history and ensure that they do not disappear. He does this best in his article for Infantry magazine, “Forgotten Soldiers: The Other 16 at Chatel-Chéhéry.” In this article, Gregory sets the scene according to the archaeological evidence, and the accounts of the men in their later statements, affidavits, and correspondences.

Gregory highlights that the entire seventeen-man crew would capture the first set of prisoners, and this equaled up to 90 of the 132 prisoners. When the machine guns opened fire, he points out that most of the men were still down in the ravine with the prisoners, and several prevented them from escaping at point of bayonet. According to later statements, several even returned fire alongside Alvin until the situation was under control.

So how is it possible that these records and accounts have been overlooked and forgotten to time? With so much evidence existing (much of it new) to prove that Alvin was not the “one-man army” so popularly envisioned, why has the story not shifted to become more accurate?

Dr. Birdwell of Tennessee Tech has built a cohesive approach to the story of Alvin York’s life and legacy within his article, “Alvin York: The Myth, The Man, The Legacy.” As curator of Alvin’s private papers, and a close collaborator with the Sergeant Alvin C. York State Historic Park, the state park built on Alvin’s original acreage, Birdwell has a unique view of more than just who Alvin was, but also how he is viewed today.

In this article, Birdwell argues that several key factors contributed to Alvin’s meteoric rise to fame, and the subsequent erasure of his companions. Birdwell argues that the perfect alignment of factors meant that the scene was right for Alvin to be the one chosen for fame and for the others to be forgotten, and an analysis of his life makes these factors clear. According to Birdwell, “what he did that day has been enlarged upon, exaggerated, and misrepresented.”

It was George Pattullo who first made Alvin famous, publishing the previously mentioned Saturday Evening Post article. Pattullo chose to focus only on York, since he was the seeming “hero,” and the story’s sensational capacity appealed to his journalist’s ability to smell an invaluable scoop. Thus Pattullo was one of the first to single out Alvin and to brush over the other men present on October 8. This effect was worsened as other journalists and authors picked up the story.

The Army chose to honor Alvin with the Medal of Honor (part of the reason that Pattullo was even present to speak with Alvin for his story after a quick review in February of 1919, and subsequently chose to offer little by way of compensation or recognition to the other men. As stated earlier, it would not be until later that any of the other designated leaders of the squads would receive their awards (and these were all lower levels than York’s).

Upon returning to the states, Alvin was approached by countless offers for the use of his image in return for monetary funds equaling up to several million dollars. He turned them all down, making it clear that he had one interest: returning home and resuming life as close to what it had been for him beforehand. When interviewed, he said that he had a girl waiting for him. When he made it back, he almost immediately married Gracie Williams and settled into a small cabin next to his mother’s.

This simplicity doubtless appealed to the American populace. In times full of uncertainty, a simple story of a man who loved his girl and took care of his mother hearkened to a quieter time that was tinged with nostalgia. As well, Alvin’s hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the Upper Cumberland was reminiscent of such American legends as Davey Crockett and Daniel Boone. For the typical urbanized American following York in the papers, he must have seemed like a real-life long hunter, a larger-than-life character compared to the crowded sidewalks and smog-filled air of large cities.

Alvin was the only conscientious objector within his group, and this also sparked public interest. The concept of a pacifist suddenly becoming a war hero was fascinating and embodied the idea of beating war and the draft at its own game. For the average American, the draft was not a treasured aspect of life, and the irony of the situation would not have been missed. Alvin was a character with whom they could sympathize with and celebrate his victories.

Another aspect of Alvin’s life that affected how he was perceived by the public was how he chose to speak about his time in the war. Any speeches or dialogues we have of Sergeant York represent his time in the Great War with fondness and fall in line with the generalized accounts of a man who was treated well by the conflict. At first however, Alvin was hesitant to share about his time in the war, viewing his aim of bringing education to the Upper Cumberland area as more important than entertaining a crowd. To York, it was more important to ask for funds for schools than to tell of his days overseas. The war was merely a chance for him to learn of a bigger world, and he wanted everyone who listened to him to realize how vital it was to offer this bigger world to every child.

Unfortunately, crowds were fickle, and having come to hear a war hero, unmet expectations of war bravado meant that Alvin had poor turnouts for his fundraising campaigns. Unable to meet projected fundraising goals, York had to rethink his strategy. Eventually, in light of bolstering numbers, he chose to bow to public demand and began to share his war stories. Crowds flocked, and fundraising became a possibility once again. Thus, the idea that Americans have of Sergeant York is at least in part thanks to his own image building to market his philanthropic work.

Another factor that few choose to address is that Alvin was the only one who was a “true American.” Alvin was touted as an icon of Americanism at its finest: a backwoods man like Abraham Lincoln, a man just as likely to pick up an axe and chop wood as pick up a gun to protect his family. This image echoed back all the way to the days of revolution, when minute men dropped their trades to file into rank to protect America from the dreaded English redcoats. Such an image, conjured by sensational news articles and a well-placed film, rendered Alvin a national legend and typecast of the ultimate patriot.

While Alvin was the “real deal,” this was not the case with his compatriots—at least, not according to public opinion. The other men eventually became or were already citizens of the United States on October 8, but most of them were immigrants or first-generation Americans with very foreign last names. Donahue was an Irish immigrant, Muzzi was Italian. Sok, Early and Muzzi became citizens only after the war. Of the others, though information may be scarce, their own last names still greatly reflected their families’ origins. Drawing from ancient roots of skepticism towards immigrants, these men were not as desirable or as marketable. As Irishmen, Donahue and Early were likely Catholic, a religion that was not popular in America. Eastern and Central Europeans, such as Konotski most likely was, were already viewed with suspicion as lesser nations that were too close to the Russian powerhouse. Foreign sounding last names like Sok and Sacina would have raised eyebrows and were not as phonetically easy to pronounce as York.

According to Birdwell, these men all came from “north-eastern urban industrial centers.” They were not novel like Alvin’s rustic charm, but the typical American story of the day, further rendering them unexciting pieces of news. Combined with the fact that these men often kept silent about their time in the war, this meant that they were often viewed as “just another veteran.”

Alvin himself may have faded from the public eye for a time, but this changed when the Sergeant York film was released. While a massive hit, the movie brought its own troubles to the muddy water. As Birdwell argues, “Cooper has come to embody, for most Americans, the essence of Sergeant York.” No longer do people remember a chatty Tennessee boy, but a quiet, reserved, and steely-eyed marksman of the character the movie made him out to be. It is possible that the public might have had the chance to view the Other Sixteen within this film, but with their refusals, all chance that these men would be represented on the big screen died for good.

And finally, another factor to be considered as far as the forgotten Other Sixteen is that of the controversy itself. When these men began to advocate for representation and recognition, they came forth with a quite different story from the one popularly held. This led to them being viewed as troublemakers and conspiracy theorists, bitter at Alvin and hoping to get back at him. For example, as Merrithew conversed with G.E. Buxton in an attempt to receive the Silver Star, he was encouraged to stay away from “purely controversial or disputed points and take the attitude that there was glory enough for all the leaders in this exploit.”

Overall, these factors combined to create a story that bolstered around one character. From his seeming contradictions to his nostalgic lifestyle, this character was the right mix to stir the public interest and hold its attention for decades after the initial events that catapulted him into the limelight.

Despite these factors however, it is vital to remember the other men who were present on October 8, 1918. The Other Sixteen were dubbed “the men who went through hell with Sergeant York,” but this is not an accurate title. Instead, it should be remembered that they all lived through hell that day and continued to live through it as soldiers during the Great War.

Through archaeological evidence and primary sources, it has been made clear that these men were more than just bystanders to Alvin’s heroism, and indeed, it was their assistance that helped him achieve fame. Had Private Wills not remained on the ground with the prisoners and stopped them from escaping, Corporal York would never have been credited with 132 captures and would never have become a sergeant. If Early had not taken York as part of his patrol, he would never have been involved in the firefight on Hill 223 in the first place. Together, this seventeen-man patrol captured an astounding number of enemy soldiers, and those who survived marched the prisoners back to regiment headquarters.

While many factors contributed to Alvin’s fame, it is a shame that he is the only one remembered for the battle over Hill 223 in the Argonne Forest. As has been previously stated several times within this thesis, glory shared is not glory lost. While Alvin has been painted as an all-American, it is to be argued that the men who served with him were just as all-American as he was. This story does not become weaker for other characters, but becomes stronger, as the American public is able to celebrate still more heroes of the War to End All Wars; men who gave their all to keep their families and nation safe and secure, even unto death. These other men, the Other Sixteen, therefore, deserve just as much recognition as Sergeant York for October 8, 1918, and it is time the American public gave it to them.

References

Birdwell, Michael E. Celluloid Soldiers: The Warner Bros. Campaign Against Nazism. New York: NYU Press, 1999.

Birdwell, Michael E. “Alvin Cullum York: The Myth, The Man, The Legend.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly. No. 4, Vol. 71. (Winter 2012): 318-339. https://jstor.org/stable/42628278

Buxton, G. E. Letter to Otis Merrithew. October 18, 1929. The Other Sixteen Private Collection. James Gregory, Midwest City, OK.

Gregory, James. “Forgotten Soldiers: The Other 16 at Chatel-Chéhéry.” Infantry, No. 2, Vol. 109. (Spring 2020): 39-43. https://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2020/Summer/pdf/12_Gregory-O16.pdf

Gregory, James. “The Other Sixteen.” Last accessed February 1, 2022. http://www.theothersixteen.com/

History.com. “Meuse-Argonne Offensive Opens.” On This Day In History. Last accessed, March 1, 2022. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/meuse-argonne-offensive-opens

Hyclak, Anna. “Sgt. York got the glory—with help, they say.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 8, 2008. https://www.inquirer.com/philly/hp/news_update/20081008_Sgt__York_got_the_glory_-_with_help__they_say.html

Kelly, Michael. Hero on the Western Front: Discovering Alvin York's WWI Battlefield. Barnsley, England: Frontline Books. 2018.

Legg, James B. “Finding Sergeant York.” Legacy, Vol. 14, Issue 1, 2010, pages 18-21.

The National Archives. “The Meuse-Argonne Offensive.” Last accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/meuse-argonne.

Nolan, Thomas J. “Where Sergeant York Won His Medal of Honor: An Example of Applied Geographic Information Science.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly. No. 4, Vol. 71. (Winter 2012): 294-317. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42628277

Pattullo, George. “The Second Elder Gives Battle.” The Saturday Evening Post. No. 43, Vol. 191. (April 26, 1919): 1, 4, 71, 73-74.

Posey, Brad. “Re-Fighting the Meuse-Argonne: Alvin York and the Battle over World War I Site Commemoration.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly. No. 4, Vol. 71. (Winter 2012): 276-293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42628276

Skeyhill, Thomas J. Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters. St John, Indiana: Christian Book Gallery, 2000.

Sok, Feodor. Letter from Feodor Sok to Edward C.B. Danforth, May 16, 1933. The Other Sixteen Private Collection. James Gregory, Midwest City, OK.

Talley, Robert. “The Men Who Went Through Hell With Sergeant York.” Healdsburg Tribune, No. 8, November 9, 1929. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=HT19291109.2.32&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------.

Tennessee Virtual Archive. “Sergeant Alvin C. York.” Last accessed March 23, 2022. https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15138coll10/id/0

US Department of Labor Naturalization Service. Bernard Early Petition for Naturalization. April 7, 1919. Sergeant Alvin C. York State Historic Park Archives, Pall Mall, TN.

Van Meulebrouck, Stephan. “Hot on the York Trail?” The Western Front Association Bulletin. No. 84 (June/July 2009): 27-31.

War Department. Beardsley Affidavit. October 23, 1918. Sergeant Alvin C. York State Historic Park Archives, Pall Mall, TN.